Background

Found throughout Canada's west coast, the Chinook Salmon (or King Salmon) is one of Canada’s most iconic fish species. Salmon are born in freshwater and undertake long migrations to saltwater to feed and mature to adulthood. After a few years in the ocean, salmon swim back up their home rivers and use their keen sense of smell to return to their birth sites to spawn. The Chinook Salmon life cycle ends after spawning, and their nutrient-rich bodies provide a critical resource for inland ecosystems. Salmon are also an invaluable component of Indigenous culture, and they support economically valuable commercial and recreational fisheries in Canada. Currently, salmon populations are threatened by overfishing, habitat fragmentation and climate change, among other factors. Many populations have been lost to extinction, while others are in severe decline.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada has completed assessment on 15 populations of Chinook Salmon in Canada and determined that 13 are Threatened or Endangered. Policy at the provincial and federal level falls short at protecting salmon runs (or migration routes) from both habitat fragmentation and over-exploitation in commercial fisheries. The Canadian Wildlife Federation is working with committed government and industry partners to improve the status of local salmon populations through research and outreach. CWF is also taking a broader-scale approach at identifying barriers to salmon migration in Canada.

In the News

Program Overview

The Canadian Wildlife Federation is using research and advocacy to learn more about Chinook Salmon behaviour, to evaluate the impacts of barriers on salmon migrations, to identify important habitats for the species, and to increase support for protecting and recovering the species.

Key Achievements

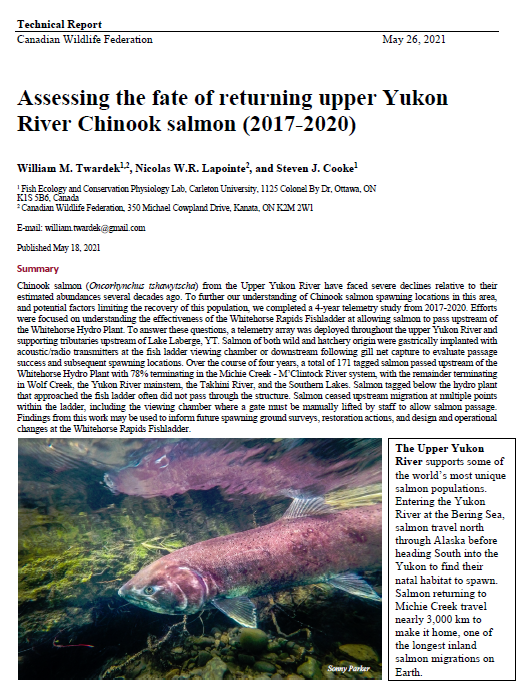

- Since 2016, CWF has partnered with Carcross/Tagish First Nation, Kwanlin Dün First Nation, Ta'an Kwäch'än Council, Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, Yukon Energy Corporation, Carleton University, Environmental Dynamics Inc., Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Yukon Fish and Game Association to develop a four-year research project on the migration of Chinook Salmon in the upper Yukon River and the potential effects of barriers on this species. Through this research, we have:

- Identified spawning sites of Chinook Salmon in the Upper Yukon River

- Evaluated the effectiveness of the Whitehorse Rapids Fishladder pilot studies to assess the effectiveness of fishways for Chinook Salmon

- Conducted Chinook Salmon carcass surveys to understand the condition of fish downstream of the Whitehorse Hydro Plant

- In 2018, CWF created a series of short films highlighting the work happening in the Upper Yukon River, and gave presentations to local communities on the conservation concerns for Chinook Salmon.

- In 2019, CWF began building a database of barriers across rivers in Canada that may affect salmon movements.

- In 2020, CWF began to develop a tool to help decision makers prioritize barriers on a watershed basis based on the amount of habitat they block, the ecological benefit and costs of remediation.

- In 2021, CWF gave several media interviews and hosted presentations to local Yukon partners about the conservation implications of the four year research project in the upper Yukon River.

Videos

Identifying Chinook Salmon Spawning Sites in the Upper Yukon River, Yukon Territory

Are salmon spawning in unknown locations?

About the project: The Canadian Wildlife Federation partnered with Carcross/Tagish First Nation, Carleton University and the Yukon Energy Corporation, among others, to identify spawning sites used by Chinook Salmon in the upper Yukon River.

Goal: Our goal was to identify spawning sites used by Chinook Salmon in the upper Yukon River near Whitehorse, YT. This included understanding whether Chinook Salmon are using spawning grounds where the species was once abundant, and whether there are new or previously undocumented sites.

History: In the summers of 2017 to 2020, we put small transmitters into adult Chinook Salmon to track their movements in the upper Yukon River. These transmitters were detected by receivers placed in strategic locations along the salmon’s migration route. We found that salmon spawn primarily in small upstream tributaries, particularly the M’Clintock River and Michie Creek, a known important spawning area. We also confirmed fish returning to Wolf Creek, and making exploratory forays further upstream into the Southern Lakes. Collectively, our work increased understanding of where salmon spawn in this key system.

Future: We are raising awareness of habitats upstream of the fishway which may be candidates for restoration or protection.

Learn more by reading the technical report "Assessing the fate of returning upper Yukon River Chinook salmon, 2017-2020"

Assessing the Efficiency of Chinook Salmon Passage Through the Whitehorse Rapids Fishladder

About the Project: The Canadian Wildlife Federation is coordinating a project to study the effectiveness of the Whitehorse Rapids Fishladder for allowing Chinook Salmon to move upstream to spawning sites beyond the Whitehorse Hydro Plant dam.

Goal: Our goal is to determine whether some Chinook Salmon that approach the dam are unable to find and move through a fishway intended to pass the fish upstream. By learning more about how Chinook Salmon behave when approaching the hydro plant, and when moving through the fishway, we hope to better understand why some salmon do not successfully pass the dam. We are also monitoring where salmon go after passing the dam and fishway, and whether they still have the energy to make it to spawning sites. We are also looking into what happens to the salmon that fail to pass the dam, and how their migratory journeys are impacted when they are unable to reach natal spawning habitat.

History: From 2017-2020 we deployed tracking receivers around the Whitehorse Hydro Plant and Whitehorse Rapids Fishladder and captured and tagged salmon with tracking transmitters downstream. Historically low runs challenged the research team to collect and tag enough salmon to complete the study, but many long days on the river made this project successful. After four years of work, it is clear many salmon fail to successfully use the fishway and pass the hydro plant. Now, the focus of this project is on understanding why that may be the case, considering the implications of this work for salmon conservation, and identifying research questions that could be addressed next.

Future: We are currently sharing and discussing our results with our project partners, including local First Nations and fishway operators. There is positive discourse on what steps can be taken to improve the fishway design and operation during future salmon runs to help more salmon complete their journeys.

- By the numbers:

- ~20,000 km of migration data analyzed

- 550 hours of gill net fishing for salmon completed

- 231 salmon tagged with transmitters

- Five salmon spawning sites identified or confirmed, with two others suspected

- Eight organizations and many individuals provided with training and experience in handling and tagging fish

- 30 individuals from several community organizations and youth from the CWF Canadian Conservation Corps involved with fieldwork and co-ordination

Surveying salmon after the end of their lifecycle in the Yukon River

What happens to salmon that fail to pass the Whitehorse Hydro Plant and reach natal spawning habitat?

About the project: The Canadian Wildlife Federation is working with local partners to collect salmon carcasses in various locations in the Yukon River to gain insight on spawning success of salmon that are unable to pass the Whitehorse Hydro Plant.

Goal: Our goal was to compare the spawning success of salmon downstream of the Whitehorse Hydro Plant to salmon in other more natural, free-flowing areas of the Yukon River watershed. By learning more about how effectively salmon spawn in natural systems, we can begin to understand the consequences of the hydro plant on salmon spawning success.

History: In 2017 researchers realized that an abundance of salmon carcasses were washing up downstream of the hydro plant. In taking a closer look at these carcasses, they found most of them had not spawned successfully. From 2018-2020, more focused efforts were made to collect salmon carcasses below the hydro plant and at other locations, so we could understand if low spawning success was unique to the area below the hydro plant. Our focus was on salmon females, as it is easy to count and estimate the number of eggs retained within their body after death. Our findings indicate that salmon females tend to retain a lot more eggs downstream of the hydro plant than in other areas of the Yukon River without a hydro plant immediately upstream. It is encouraging however, that salmon that fail to pass the WHP may still find a way to spawn, even if it is at a less suitable location, and to a lesser extent.

Future: We are continuing to analyze the carcass survey data and are discussing with local organizations how these surveys could be continued in the future.

Learn more by reading the technical report "Survey of Chinook Salmon carcasses in Whitehorse, Yukon – 2020"

Species Facts

Chinook Salmon - Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

The Chinook Salmon is a large-bodied species that completes an extensive round-trip migration between freshwater and saltwater to complete various stages of its life cycle.

Habitat: Chinook Salmon are born in freshwater but leave to the coastal and open ocean to feed. They then return to spawn in the exact streams where they were born many years ago.

Range: Chinook Salmon are native to the Pacific Ocean and the streams that flow into it from California to Alaska, as well as from Russia. They have been introduced to the Great Lakes, South America and New Zealand, where viable populations exist.

Did You Know?

Chinook Salmon are also known as “King Salmon because they are larger than all other salmon species, reaching over 100 pounds!

Adult Chinook Salmon may swim up to 3,200 km upstream to complete their spawning migrations, moving at a rate of ~50 km per day!

Adult male salmon develop a large hooked nose called a “kype.” The function of this structure is not fully understood, but is believed to help males compete for females.

Next Steps

Additional Resources

Reports and Papers

Program Lead

Nick Lapointe

Nick Lapointe works at the Canadian Wildlife Federation as the Senior Conservation Biologist – Freshwater Ecology. Originally from Ottawa, he completed his doctorate at Virginia Tech before returning home to work in conservation. Nick studies aquatic habitat, restoration and invasive species while working to protect freshwater fisheries, biodiversity and species at risk. He spends his free time fishing, hunting and foraging in Ottawa’s hinterland.

“The Chinook Salmon is an iconic Canadian species and one of our most revered fish. Today, salmon fisheries are not what they once were. Due in part, if not primarily, to decades of selective harvesting of the largest individuals, the largest Chinook Salmon are now extremely rare and have disappeared from many populations. Sadly, even more fisheries continue to close because of population decline. We need to better conserve and restore Chinook Salmon habitat and better manage the harvest of this species to ensure its recovery.”

Blogs

More Pacific Salmon and Trout Can Now Go Home

More Pacific Salmon and Trout Can Now Go Home

Broad Scale Efforts Underway to Restore Fish Passage Across B.C. An elevated stream culvert may mean nothing more than simple road maintenance to us. But to a Pacific salmon desperately… Read

Sign Up for Timely Articles and Tips

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3