Insects are a diverse group of animals that provide many ecosystem functions that support life on earth. However, despite their important roles, insects have often been shunned. Understanding how they live and being able to tell them apart can go a long way in feeling safer outside, enjoying the incredible biodiversity at our doorstep and wanting to help support these tiny allies.

Many thanks to Jeff Skevington, Adjunct Research Professor, Research Scientist, for contributing this content

Background

Flies are one of nature’s most diverse groups of organisms. Over 162,000 species have been identified and likely well over a million species currently exist on our planet! They perform virtually all known ecosystem roles in land-based and freshwater ecosystems to the extent that our planet would not exist in its present form without flies.

We tend to associate flies with a single species, the House Fly (Musca domestica). This species has spread worldwide from a presumed Middle Eastern origin and is a nuisance and vector of diseases. Mosquitoes, black flies and fruit flies all add to the negativity associated with flies. However, only a tiny fraction of fly species are considered pests. Most go about their business regulating our environment without notice or congratulations. If we just look around our gardens, we can begin to see the immense value that flies provide, sometimes even the pesky ones. Decomposers like soldier flies work away on our compost heaps. Others contribute to the turnover of branches, leaves, twigs and logs. Many species, including some flower fly immatures (called larvae), live in ponds and other wetlands and filter feed on bacteria. Sewage lagoon health is heavily determined by flower fly larvae that feed on the abundant bacteria! Many flies are predators as larvae and keep potential pests under control.

The overwhelming prevalence of bee information would have us believe that bees do all our pollination but most of our pollinators in temperate parts of the world like Canada are actually flies! Even the pesky House Fly, mentioned above, is a pollinator. The further north you go, the more plants are reliant on flies for pollination. There are many groups of pollinator flies, but the best-known group is the flower flies (Syrphidae).

How to Recognize Flies

Almost all adult insects have two pairs of wings. Except for flies. Flies have a single pair of wings and have had their hind wings modified into structures called halters. They spin these halters as they fly, functioning much like the gyroscopes on helicopters, feeding information on the individual’s orientation back to the fly. As a result, flies are amongst the most spectacular of the flying insects with many capable of hovering in one place for minutes at a time or even flying backwards like hummingbirds. If you can see the halters, you know you are looking at a fly.

Some wasps and bees keep their wings together so it can be hard to count the wings. If you are not sure if you are looking at a fly or bee, look at the face and antennae. Flies never have long, thread-like antennae that wasps and bees have. Fly eyes tend to also fill most of their head while bee and wasp eyes are smaller. Many of our flower visiting flies mimic bees and wasps so you need to have a close look at them until you have figured out the subtle differences.

Mimicry

Why mimic bees and wasps? Most bees and wasps protect themselves with a stinger and have developed bright colouration as a warning to would-be predators to stay away. Flies don’t sting but many have copied both the colouration and behaviour of wasps and bees to gain protection. Larger flies are often near perfect mimics of a particular bee or wasp species, presumably because the bigger the fly, the more valuable it is as a food resource for birds. Smaller flies are often imperfect mimics. This is presumably enough to warn off predators and their small size doesn’t warrant giving them a second look.

There are amazing mimics you can see in your garden from several families of flies. Robber flies (Asilidae), bee flies (Bombyliidae), thick-headed flies (Conopidae) and particularly flower flies (Syrphidae) have lots of superb mimics.

Fly Families

There are over 160 families of flies in the world. Some of these families are incredibly diverse. For example, gall midges (Cecidomyiidae) and scuttle flies (Phoridae) are both considered dark taxa (groups of animals that have so many species we don’t even know how to estimate the diversity). There are over 6,600 species of gall midges identified and over 4,000 species of scuttle flies but there could be hundreds of thousands of species in each family! Most fly families have narrow and well-defined ecological roles, but scuttle flies are remarkable in that they do almost everything. There are decomposers, predators, plant-eaters, fungus feeders, and parasitoids (parasitoids develop inside other insects ultimately killing their hosts). The only other family of flies that has developed this level of ecological flexibility are the flower flies (Syrphidae).

Below are some of the groups covered, to help get you started.

How Can I Learn More About Flies if They Are so Diverse? Where do I Start?

The advice from Jeff Skevington, Adjunct Research Professor at Carleton University is to pick a family of flies that grabs your interest and start there. It is overwhelming to try to tackle them on a broad front. Jeff has specialized on three families of flies over his career and he feels that is more than enough diversity to try to get a handle on! One of these families, the flower flies, offers a nice starting point as the species are quite recognizable. An added advantage is that there is a field guide to the eastern species (The Field Guide to the Flower Flies of Northeastern North America) that really helps get you started. It will even help in western Canada despite not covering all the species there.

General Identification Aids

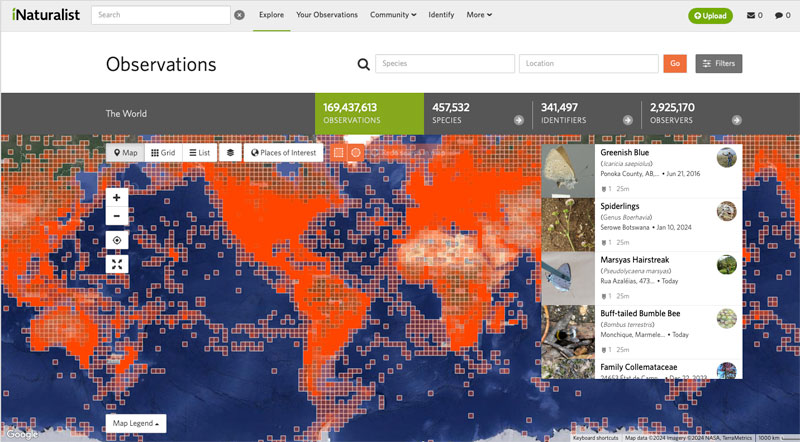

Identification of most flies to species is tricky but, with the exception of bristle flies, the groups highlighted here are manageable and fun to get to know. The Field Guide to the Flower Flies of Northeastern North America, as mentioned above, is a great starting point for that family and allows you to flip pages and easily compare species. The best app to use for identification of these groups is iNaturalist Canada. You won’t always get the key characters in your photos, but you will quickly learn what is needed to narrow down photos to species. iNaturalist Canada works by comparing your photo against a massive library of identified photos and providing likely matches. You can then compare your animal to the possibilities proposed and choose the best match. Other observers then weigh in and either agree or make suggestions to the identification. Another app called Seek works with the iNaturalist platform and is very fast but does not have the benefit of feedback from the online community. If you cannot figure out your fly on iNaturalist Canada, BugGuide is another excellent online resource to fall back on. This community of experts will very often be able to help where iNaturalist Canada could not. Watch for more field guides in the future as the demand for resources on wildlife continues to grow. It is an exciting time for naturalists!