Not all plants are seed-producing plants (known as spermatophytes) but most fall into two major groups: the flowering plants and the conifers. Of the more than 230,000 known species of plants worldwide, about 200,000 are flowering plants; another 500 are conifers while others include such plants as ferns and mosses. Most seed-producers owe their great success, in part, to pollination.

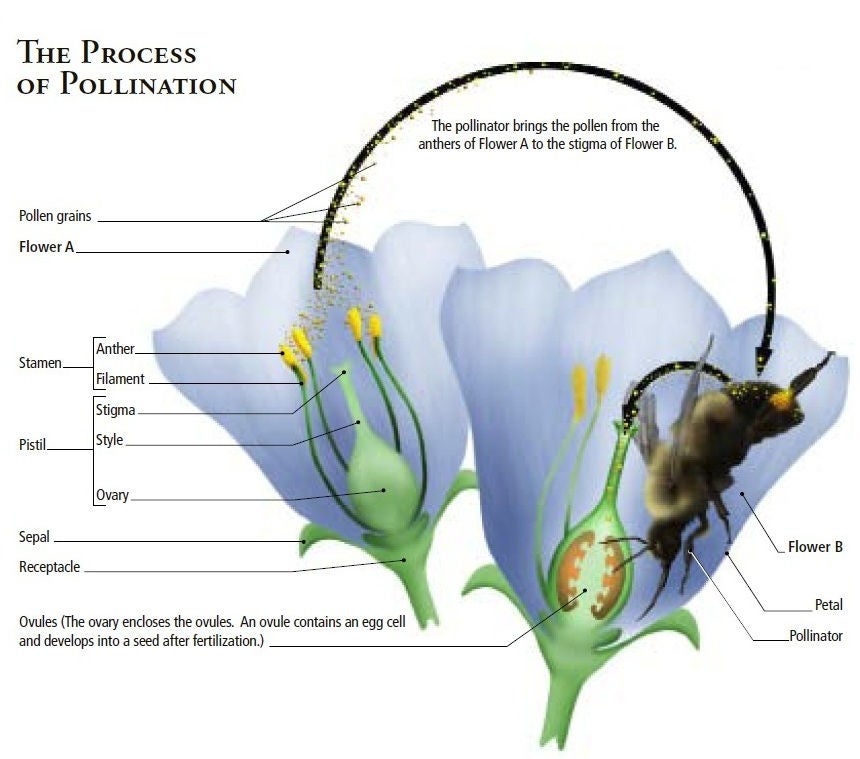

Flowering plants (angiosperms in science lingo) include broadleaf trees and all of our familiar garden vegetables, rice, wheat and other grains — almost every plant we use for food. They keep their reproductive parts deep inside an often showy display of petals. Anthers, which top off the stamens, produce the male pollen. Ovaries produce female egg cells and sit at the base of the pistil (which includes a "landing area" for the pollen called the stigma). Pollination for flowering plants is the process of bringing the pollen from the anthers to the stigma where it can find its way down the pistil to the eggs in the ovary. Eggs fertilized in such a manner develop into seeds, and the surrounding ovary becomes a fruit.

The conifers (known as gymnosperms) include such trees as the pine, spruce and fir that dominate many Canadian landscapes. Gymnosperms don't have flowers; they produce male and female cones. Seeds are produced when pollen grains from the male cones fertilize eggs on the female cones. The seeds grow up naked on the cones without ever developing fruit

Some plants can self-pollinate (a process called autogamy); others must cross-pollinate (syngamy) to produce viable seeds. In autogamous plants, pollen moves from the male to the female part of the same flower or the same plant and then fertilizes an egg cell. In syngamous plants, seeds are produced only when pollen from one plant combines with the eggs of a different plant of the same species. Syngamous plants must have a partner nearby! There are a few species of flowering plants, such as the dandelion, that can produce seeds without pollination

Matchmakers

Pollen cannot move on its own. Different types of plants depend on different agents to bring male pollen to meet the right female egg. Living agents, called biotic pollinators, do about 80 per cent of the work. Insects such as bees, butterflies and beetles are the most important biotic pollinators and, in Canada, animals such as hummingbirds also get in on the act

Non-living (abiotic) agents — wind and water — are important pollinators for some types of plants. Grasses, corn and some trees, such as pines, rely on the wind to transfer pollen. These plants produce huge amounts of pollen to maximize the chance for pollination to occur. For example, pine pollen can be so thick in the air that it can be seen as long, yellowish clouds streaming off the trees on a windy day. Water, the least common way to move pollen, is mostly used by aquatic plants.

Adaptations

Through time, seed-producing plants have adapted and specialized to take better advantage of particular agents of pollination. The pollen of plants that rely on wind, for example, is often small, lightweight and highly exposed for easy pickup. These plants produce pollen at times when there are fewer leaves to block wind currents

In the spirit of a true partnership, living pollinators, such as insects and hummingbirds, have also adapted along with their favourite plants. Plants that rely on insects or other animals for pollination often have sticky pollen that can be picked up on visiting beaks, bodies and wings but they must also employ a strategy to attract — and keep — business. Flowers are perfect for creating an attention-grabbing "ad campaign" and, usually, offer rewards for loyal customers — protein-rich pollen and sweet nectar. Here are some self-promotion strategies:

- Colour: Most flowers use specific colours and colour combinations in their petals to capture the pollinator's interest. But different types of animals see colour differently and have different preferences For instance, bees see in ultraviolet, most insects are attracted to flowers that are blue, mauve, purple or yellow, while hummingbirds go for red hues. The colour pattern is also important. Many petals incorporate colourful stripes, like landing lights at an airport, to lead an insect into the flower where the pollen is waiting.

- Shape: Flower shape plays a big role in determining which species of pollinator can get to where the nectar is stored. Open, broad flowers such as asters and daisies provide a "landing pad" for butterflies. Trumpet-shaped flowers, such as the morning glory, cater to hummingbirds that can hover while they poke their long, thin beaks deep into blossoms. The twisted form of the snapdragon favours tiny insects that can penetrate small spaces. Monkshood has tightly closed flowers that only the strongest pollinators, such as bumble bees, can force their way into. Some Arctic and alpine flower petals are light-coloured and elliptical, which enables them to bounce light into the centre of the flower and attract pollinators with heat.

- Scent: The smell of flowers can also lure some pollinators. Butterflies tend to be attracted to flowers with the weakest scent; nocturnal moths are attracted to those with heavy scents Some flowers smell downright foul to us The red trillium, for instance, has evolved to attract flies. What better way to do so than to mimic the colour and smell of a fly's favourite food — rotting meat?

- Timing: Some flowers open only at night and are light-coloured to better attract nocturnal pollinators. The flowers of some orchids, though open in the day, only produce scent at dusk when their pollinators are active. While some pollinators can get food from a diversity of plant species, others are very specialized and rely on one. For example, the yucca moth depends on the yucca plant (soapweed) for food, and the yucca plant depends solely on this moth for pollination services

Flowering plants (angiosperms) include broadleaf trees and all of our familiar garden vegetables, rice, wheat and other grains — almost every plant we use for food. They keep their reproductive parts deep inside an often showy display of petals. Anthers, which top off the stamens, produce the male pollen. Ovaries produce female egg cells and sit at the base of the pistil (which includes a "landing area" for the pollen called the stigma) Pollination for flowering plants is the process of bringing the pollen from the anthers to the stigma where it can find its way down the pistil to the eggs in the ovary. Eggs fertilized in such a manner develop into seeds, and the surrounding ovary becomes a fruit.

Some plants can self-pollinate (a process called autogamy); others must cross-pollinate (syngamy) to produce viable seeds. In autogamous plants, pollen moves from the male to the female part of the same flower or the same plant and then fertilizes an egg cell. In syngamous plants, such as shown in this illustration, seeds are produced only when pollen from one plant combines with the eggs of a different plant of the same species. Syngamous plants must have a partner nearby!

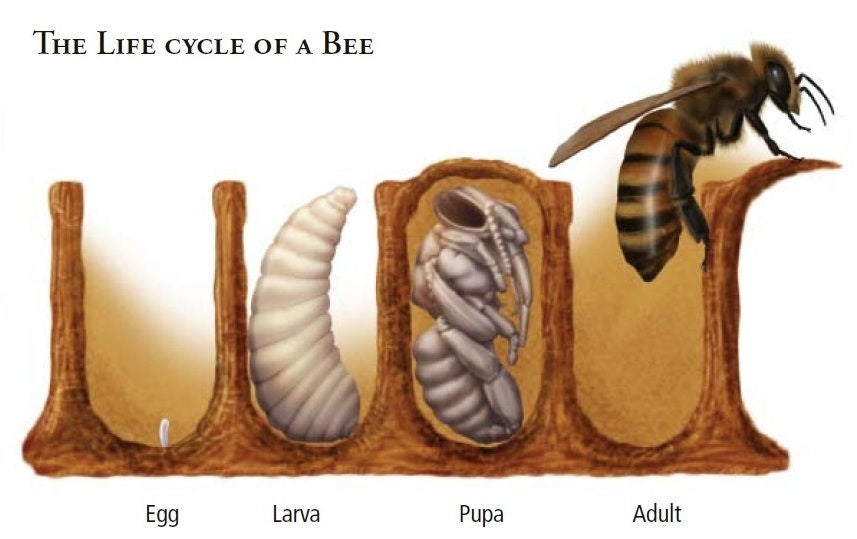

The life cycle of a bee has four stages — egg, larva, pupa and adult. The female bee creates cells within the nest that are lined and then provisioned with pollen and nectar as food for the larvae. She then lays an egg within each cell where the larva can safely develop.

Copyright Notice

© Canadian Wildlife Federation

All rights reserved. Web site content may be electronically copied or printed for classroom, personal and non-commercial use. All other users must receive written permission.