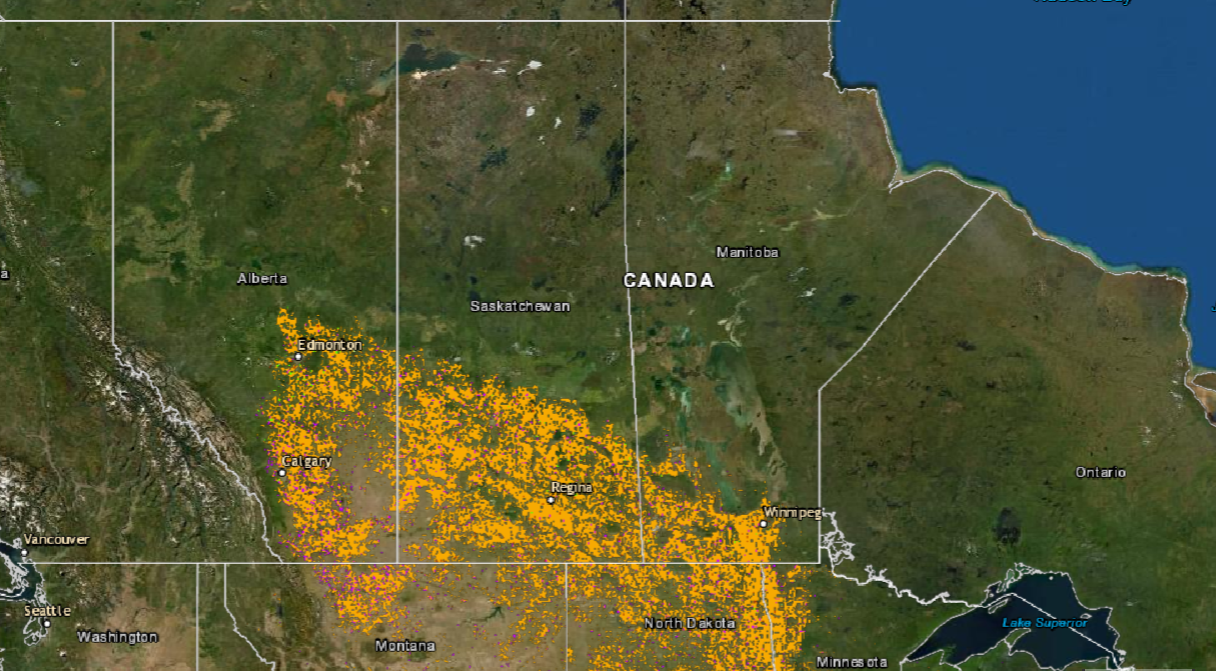

The Canadian Prairie ecozone: roughly 465,094 km2, which is almost 5 per cent of Canada’s landmass. This is 16 per cent of the Great Plains of North America.

Extraordinary Grasslands

Grasslands are extraordinary wildernesses that are among the world’s most endangered ecosystems. The diversity of wildlife species on grasslands has been replaced by crops, roads, oil and gas development and sprawling cities and towns. Less than 20 per cent of native grasslands remain and what is left is critical habitat necessary to recover declining species at risk like the Burrowing Owl, Ferruginous Hawk, Swift Fox, Greater Sage Grouse, and Long-billed Curlew. CWF is working to conserve native grasslands and wildlife in SK and AB.

The Great Plains once stretched unimpeded from Mexico to Canada, spanning southern Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Plains Bison roamed in herds millions strong, their thunderous presence carving habitat in the landscape for many species including badgers, Pronghorn, prairie dogs, grassland birds, insects and rare plants. Great Plains wolves and the prairie population of Grizzly Bears thrived on these great herds, hunting openly among flowers and grasses. Indigenous Peoples built powerful nations and rich cultures on the natural abundance of these lands, prospering for millennia. The calls of Sprague’s Pipit and Chestnut-collared Longspur signaled the start of spring, while great migrants like Snow Geese gathered in droves to rest and refuel at abundant wetlands and prairie potholes on their way to their Arctic breeding grounds.

Our Work on Native Grassland Conservation

Saving Grasslands Through Sustainable Ranching

The Canadian Wildlife Federation is working to stop the conversion of native grasslands to cropland and other uses. This includes working with cattle ranchers to protect grasslands on their land.

Learn More >

SUPPORTING THE NORTH AMERICA GRASSLAND CONSERVATION ACT

We have joined the Central Grasslands Roadmap, a working group with across-the-continent representation from Indigenous organizations, the agricultural community, NGOs, governments, and academia. We are hopeful that legislation to protect grasslands in the United States will be enacted as it will also benefit Canadian grasslands.

Learn more >

Pronghorn Xing

Natural grasslands are among Canada’s most threatened ecosystems. Movement barriers are a serious threat. Barriers, like highways and fences can stop the movements of the only large migrating mammal left on the Great Plains: the Pronghorn. Highways are a triple-threat to Pronghorn.

Learn more >

The Prairie Grassland Multi-species Project

CWF is partnering with the Saskatchewan Stock Growers Foundation and SODCAP (South of the Divide Conservation Action Program), Birds Canada, Carleton University, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada and the University of Saskatchewan to study the effects of grazing on plant community structure, insect diversity, insect abundance, and bird distribution. Launched in 2021, with its first field season in 2022, this project is funded by the generous support of the Weston Family Foundation.

Learn more >

Did You Know?

⅓

Grasslands store about ⅓ of the world’s land-based carbon, mostly in the soil.

100 tonnes / hectare

The top 60 centimeters of soil in Canada's native grasslands hold more than 100 tonnes of carbon per hectare.

70 species

There are more than 70 species at risk on the Canadian prairies. Most rely on native grassland habitats for survival.

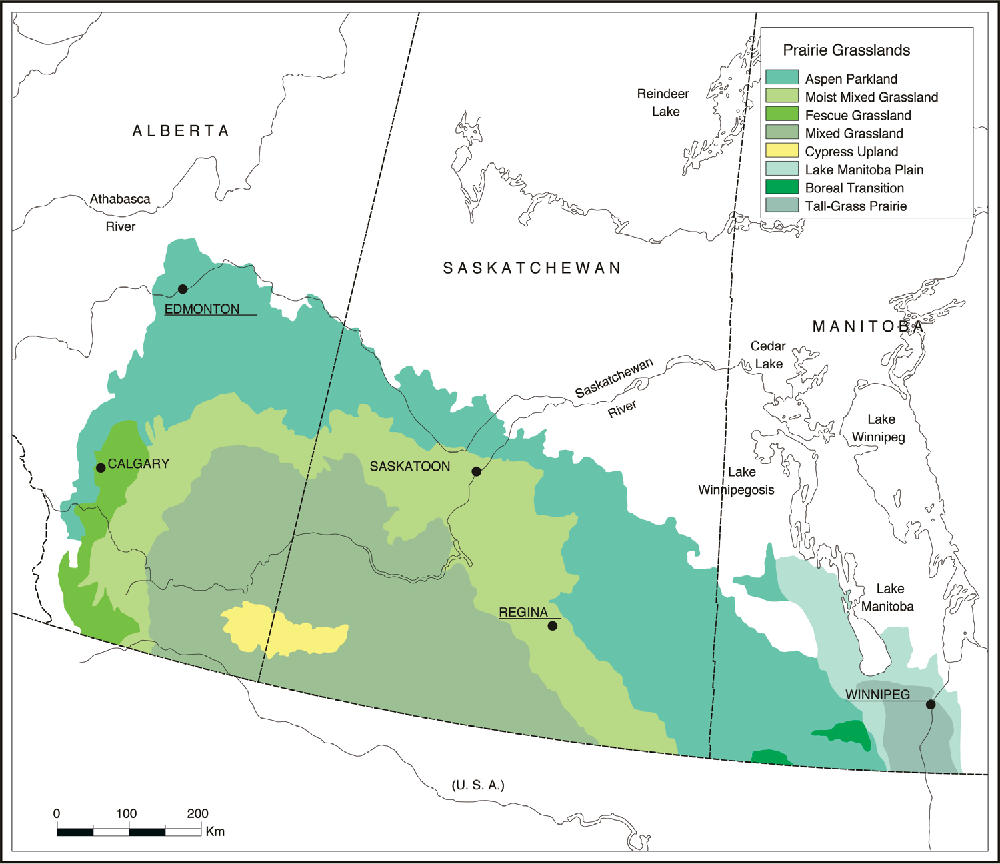

Canada's Diverse Grasslands

There are six types of native grassland in the Canadian prairies: Tallgrass and Lake Manitoba Plains found in the east where rainclouds are more generous, Moist and Dry Mixedgrass in Saskatchewan and Alberta with a drier climate and Foothills Fescue and Cypress Uplands where elevation changes everything, including soils and local weather.

Cultural significance

The Canadian grasslands have been home to Indigenous Peoples since time immemorial. The landscape and species that live on the grasslands are intricately tied to Indigenous cultures, livelihoods, medicines and food security. The native prairie grasslands in what is now known as Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba are the traditional territories of many nations, including the Siksika, Piikani, Kainai, Tsuutʼina, Stoney, Nakoda, Lakota, Dakota, Nêhiyawak (Cree), Anihšināpēk (Ojibwe/Saulteaux) and Métis Nations. The Canadian Wildlife Federation acknowledges that these native prairie grasslands are Treaties 1–7 territory and the homeland of the Métis/Michif.

For millennia, Indigenous Peoples have lived in harmony with the ecosystem of the prairies, sustainably harvesting animals, berries and plants for food, and medicines. Bison and other wildlife have also been an essential source of shelter, clothing, and tools. The importance of wildlife and grassland habitat was and is still reflected in Regalia, ceremonies, art, storytelling, dances and economic activities.

Threats

The native grasslands of Canada continue to be under threat.

Urban Expansion

- As our human population grows, cities push into grassland habitats, displacing species like the threatened Ferruginous Hawk that abandon areas too close to human settlement.

A world beneath your feet

- Grass grows quickly, but grassland ecosystems do not. When we plow the prairie, we lose biodiversity from above the surface and carbon beneath it. This can take centuries to restore. There are more than 100 tonnes of carbon per hectare in the top 60 centimeters of grassland soil. An estimated 52 tonnes of carbon dioxide per hectare have been released from grasslands in the Northern Great Plains to plant crops since 2000 alone!

Invasive Species

- Invasive plant species such as Crested Wheatgrass, Smooth Brome, Yellow Sweet Clover, Creeping Thistle and Leafy Spurge remain a significant threat to native grasslands and endanger some of the ecosystem services native habitats provide.

Forest Expansion

- On the edge of the Great Plains, forests can move in. There are several reasons for this, including far fewer wildfires to hold the forests back. Fire is a necessary and natural process that adds valuable nutrients to prairie soils, but wildfires threaten homes, buildings and fences. Prescribed fires offer a safe way to return fires to grasslands when and where they are appropriate to achieve ecological goals.

Ecosystem services

Beyond experiencing the peace that comes from being surrounded by swaying grasses, wildflowers and bird song, grasslands benefit us in many ways.

Soil is an intricate web of life that provides many services. It cycles nutrients, stores flood water, prevents surface erosion, and stores carbon. Native grassland soils can store tonnes of carbon and research to understand how soil management affects carbon storage is underway. As forests become ever more vulnerable to fire, grasslands may be a more reliable carbon sink than trees.

Prairie wildflowers support numerous pollinator species such as bees, birds, butterflies, flower flies and beetles. Some of these species are also critical for pollinating domestic crops. Wildflowers provide pollinators with nectar when crops aren’t in flower.

Prairie wetlands are not only critical habitats for many of North America’s waterfowl and other wildlife, but are key natural infrastructure that helps prevent floods, capture sediment, filter run-off and recharge groundwater. Like the rich, fertile soil of native grasslands, they also provide climate protection via carbon stores.

As climate change intensifies, healthy grasslands will be vital in supporting resilient communities in the face of droughts and extreme weather events.

Explore the Canadian Prairie Flora and Fauna

Climate Change will profoundly affect Canada’s Native Grasslands

Native grasslands are evolved to withstand exactly the kind of weather fluctuations that climate change will bring to the Canadian prairies. The wild plants and animals that still live on native grasslands are adapted to drought and flood, the extremes of heat and cold and the kinds of winds that climate changes scientists predict for the North American Great Plains.

However, less than 20 per cent of the grasslands in prairie Canada remain native. The rest have been put to the plow, paved, drilled, or mined. With these changes, resilience to climate change has evaporated. Crops, suffering through a long hot growing season will need vanishing water resources to grow. The challenge to feed cattle will grow as grass and forages wither in the dry heat. Grasslands abandoned will be more likely to grow back with shrubs that use deeper roots to tap groundwater and grow vigorously in a high carbon atmosphere. Climate change will have profound effects on Canada’s native grasslands.

Videos

In the News

Program Lead

CWF Native Grassland Conservation Manager. John’s work on native prairie grasslands includes research, policy and collaborative conservation work with ranchers and partners including Saskatchewan Stockgrowers Foundation and South of the Divide Conservation Action Program. He is a member of the Grassland Roadmap Canadian Working Group. John is an adjunct professor at the University of Saskatchewan in Geography & Planning with a focus on remote sensing in grasslands. John works closely with the Terrestrial Ecology program at CWF, led by Dr. Carolyn Callaghan, giving the Native Grassland program a national and international scope.

"Native prairie grasslands pulsate with life and culture. As native grasslands disappear, many of the benefits they provide are lost. Nature-based solutions are the key to creating resilient communities."

Related Resources

Sign Up for Timely

Articles and Tips

- 0

- 1

- 2