Dec 8, 2015

David Hayes

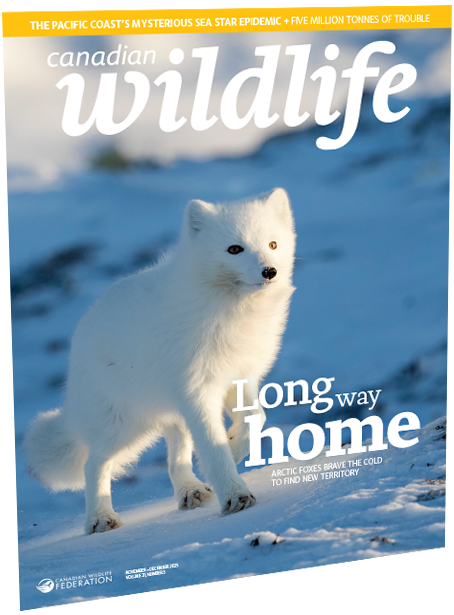

Courtesy of Canadian Wildlife Magazine

Wait! Before you read on, have you read part one of this fascinating story? You’ll want to know all the details to piece together this mystery! Read part one here.

The man at the centre of this case is an enigmatic figure. Greg Logan has a medium build and pale complexion, and grew up in Saint John, the only boy in a family of three children. After high school, he worked for the New Brunswick Telephone Co. for a year before joining the RCMP in 1978, when he was 20. After training at “Depot,” the RCMP academy in Regina, he was posted to a detachment in Valleyview, Alberta, in 1979, followed by postings to Edmonton, the Leduc rural detachment and the Leduc freeway patrol. In 1982, he was transferred to the eastern Northwest Territories (now Nunavut), where he served in Frobisher Bay (now Iqaluit) and then Sanikiluaq until 1985. From that year until 2003 he served in a variety of capacities with the detachment in Grande Prairie, Alberta.

When the case against Logan made it to the New Brunswick Provincial Court in 2013, a profile emerged of a dedicated and respected officer who had received positive evaluations throughout his career, but also one who had paid a price in the line of duty. In an affidavit filed in court, Logan described his experiences as a law enforcement officer that led to a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder in 2004. Among the events:

Extracting a human skull that was smeared to the pavement following a motor vehicle fatality and placing it into a body bag with the deceased’s remains.

Using a hack saw to separate and seize a segment of a deceased’s leg, which was frozen in ice…following an airplane crash…

Finding a deceased boy on a sand bar, whose leg detached from his body in my hands as I moved him from the scene onto a boat…

Attending on the scene of a bear attack and finding a young woman whose foot was almost totally severed and her stomach area clawed open…

Attending an industrial accident where an individual unloading wood chips from a tractor trailer unit by-passed a procedure to save time and as a result was decapitated.

Logan suffered physical injuries, too. In 1979, his cruiser hit a moose while he was on patrol, resulting in two fractured vertebrae in his neck and severe damage to his shoulder blade. (After the accident, he spent time recuperating in Saint John, where he married Nina, with whom he raised a family.) Over the years, following altercations with suspects and two more car accidents while on duty, he ended up with a torn rotator cuff in his right shoulder and a lower back injury. He also suffered hearing loss and tinnitus after a shotgun was fired through the wall of an apartment where he was investigating a crime. (Logan needed hearing aids following this incident.) After a medical examination in 2000, the RCMP determined that his injuries were serious enough that he couldn’t go back to his previous role as an officer. The force assigned him to an administrative position until 2003, when he completed 25 years of service and qualified for a pension. He was 45 years old.

It was during the early 1980s while posted to the Eastern Arctic, that Logan became aware of narwhal tusks, which can be bought in some remote communities in the gifts shops of local co-ops such as the Koomiut Co-operative Assoc. Ltd. in Kugaaruk (formerly Pelly Bay) and Naujat Co-operative Ltd. in Repulse Bay. According to the background presented by his lawyer, Brian Greenspan, in court appearances in 2013, Logan bought some tusks for himself, for family members and friends and, eventually, began selling them legally on “a modest commercial basis” within Canada.

The larger question, of course, is why Logan’s initial dabbling became an illegal enterprise. At sentencing — Logan pleaded guilty to seven counts under the wild animal and plant protection act, forgoing the need for a full trial — Greenspan reminded the judge of Logan’s long record as a law enforcement officer, explaining that after his injuries essentially forced his retirement, he “ended up with a significant impairment of his enjoyment of life and… pain and suffering that he continues to have on an ongoing basis.” Greenspan added, “that’s not meant to excuse his involvement in these offences…” although the statement suggested a link between Logan’s pain and suffering and hisdecision to make money by illegally selling narwhal tusks to U.S. clients.

“Mr Logan comes before the Court and has to, perhaps, cash out on the good that he did in the community and the contributions he made in the community and balance that against his infraction…” Greenspan continued. Logan “finds himself in a situation where he accepts… the fact that he became a law breaker rather than a law enforcer and that is indeed a terrible experience for him…”

Concluding, Greenspan said, “[U]ntil he discovered the Internet and the market for these tusks in the United States he really didn’t have any thought about exportation. And all of a sudden a modest side hobby became a bit of a supplement to his medical and RCMP pensions…”

The origins of Operation Longtooth can be traced to 2004, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was alerted by customs officials at JFK International Airport to a package, sent from Odessa by a Ukrainian named Andriy Mikhalyov, with a label that read “tooth of white whale” (a reference to Melville’s fictional sperm whale, Moby Dick). It contained 548 sperm whale teeth, which, like narwhal tusks, are banned under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. An investigation revealed that one of Mikhalyov’s clients was Nantucket-based David Place, who sold touristy, maritime-related items from his antique shop while operating a more profitable shadow business dealing in sperm whale teeth and narwhal tusks. On eBay, Place listed his products — with little subtlety — as being a “whale of a deal,” or having “a nice ivory colour.”

Among the evidence gathered by investigators and filed in courtwas a May 17, 2001 email Place sent to one of his narwhal tusk suppliers, a Canadian named Nina Logan. It read in part: “Next time we do this I would like to get whatever documents I can certifying that these were taken legally, but for now I have managed without.”

Nine days later he had another exchange with Logan:

Place: “…every time I mention the tusks to anyone they want to know if they have papers.”

Logan: “…your customers are very correct in requesting supporting documentation.”

Place: “I can still sell them without papers to other customers, but it would be wonderful if everything were above board with papers, if you know what I mean!”

No one would have a hard time parsing Place’s meaning, but the Logans couldn’t provide supporting documentation for items being smuggled into the U.S. If Place was concerned, it didn’t stop him from continuing to do business with them.

In March of 2011, Place was convicted in a Boston court of illegally importing and trafficking in sperm whale teeth and narwhal tusks. He received a 33-month prison sentence. (After being arrested entering the U.S., Mikhalyov — Place’s source in Odessa — served a nine-month sentence on related charges and was deported to the Ukraine.)

But the investigation — in the U.S., separatelycodenamed Operation Nanook — was ongoing. In January 2013, Jay Conrad, a former roofing contractor and collector of shrunken heads (who, coincidentally, lived on Canada Road in Lakeland, Tennessee, a suburb of Memphis), was arraigned on 29 conspiracy and money-laundering charges relating to the smuggling of narwhal tusks. According to U.S. authorities, Conrad and a partner who lived nearby, Eddie Thomas Dunn, paid Logan $126,000 for 135 tusks, in cheques or money orders that were sent to a mailing address in Bangor or directly to the Logans in Canada. Conrad’s windfall from marketing the tusks to buyers in Alaska, Washington State, Ohio, Florida and Tennessee was estimated to be between $400,000 and $1 million, and Dunn’s at $1.1 million. (Dunn, who would later play a key role in the investigation of Logan, plea-bargained and agreed to cooperate with authorities for a reduced sentence.)

Meanwhile, federal agents had come to realize that an informant, Andrew Zarauskas, who had been providing them with information about David Place’s illegal dealing in sperm whale teeth, was also part of the narwhal tusk conspiracy. Zarauskas, who ran a construction business, but also collected and sold antiques, bought an estimated 33 tusks from Logan between prior to 2008, according to U.S. officials. On Feb. 17, 2010, during a meeting at Café Vivaldi in Union, New Jersey, federal agents confronted him about his involvement with Logan. In an increasingly confused interview, Zarauskas said he thought the tusks came legally from existing collections in the U.S., but also claimed he didn’t know it was illegal to import tusks from Canada. At another point, unable to deny knowing the Logans, he explained that he didn’t know how Logan brought the tusks across the border (a logging truck, maybe, a boat…?) He was later convicted on six counts of smuggling and money laundering and given a 33-month prison sentence plus a $7,500 fine.

In the spring of 2009, U.S. Fish and Wildlife officers contacted Quentin Deering, at Environment Canada’s Prairie and northern region office in Yellowknife. They told him they’d learned of a Canadian who was smuggling narwhal tusks from the North to American buyers. What began as an investigation out of the northern region office — Logan’s primary residence was in Grande Prairie — shifted to the Atlantic region when it turned out Logan was operating his narwhal tusk business out of a second home in New Brunswick.

“So, we started collecting as much information about him as we could find,” says Glen Ehler, a compact, engaging 44-year-old Maritimer with a master’s degree in sociology and specialization in criminology.

For a large-scale operation like Operation Longtooth, Ehler needed to assemble a team with specific skills and previous surveillance experience. He and Deering would be the leads, coordinating with U.S. officials and documenting the operation. Two more officers were recruited from Nova Scotia, along with two from Ontario, one from New Brunswick and one from Newfoundland and Labrador.

Deering had extensive experience with the many kinds of legal paperwork required for an investigation like this. Among other things, these included search warrants and production orders (similar to an American subpoena, they compel institutions like banks, Internet service providers and phone companies to make information available to authorities). Fisheries and Oceans supplied records showing Logan’s name on a large number of legalnarwhal tusks shipments within Canada. Air Canada’s records documented Logan’s trips from his home in Grande Prairie to New Brunswick coinciding with records from Canadian Border Services Agency that his trips to the U.S. via the border crossing at Calais, Maine, matched FedEx shipments of narwhal tusks sent to U.S. buyers. Logan sometimes arranged for payments to be sent to a post office box at a UPS outlet in Ellsworth, 45 minutes south of Bangor, and he deposited them variousaccounts, including one at Maine’s Machias Savings Bank and oneat the First Bank of Conroe in Texas, where, according to Canadian investigators, he owned a third property. (In Canada, Logan had U.S. dollar accounts with Scotiabank and Alberta’s ATB Financial.)

“One thing Mr. Logan was good at was adopting different personas for all the people he dealt with,” says Kim MacArthur, one of the team of Canadianwildlife enforcement officers who worked on the file. “If you spoke to each of them separately, they’d all tell different stories about the man they knew as Mr. Logan.”

Missing, however, was clear evidence of how Logan did the smuggling. That’s why the next step was monitoring when a shipment was promised to a U.S. buyer and mounting a mobile surveillance operation to follow him across the border. That wasn’t hard to do. Eddie Dunn had agreed to a plea bargain and was helping U.S. authorities. Dunn arranged to buy tusks from Logan and alerted authorities to the deal.

After Ehler and Deering followed Logan to Bangor in August 2009, they began gathering more evidence. By the end of 2009, their counterparts in the U.S. told them that Logan might soon become suspicious, so Deering arranged for search warrants and, on Dec. 17, officers entered Logan’s home in Grande Prairie and his residence in New Brunswick. Along with seizing the Chevrolet Avalanche he’d used for the Maine trip, investigators also took a utility trailer that he often attached to the back of the truck. It had been modified with a hidden compartment suitable for concealing narwhal tusks. They also found packing materials, including shipping tubes, packing sleeves and plywood panels, identical to those found among the possessions of Logan’s U.S. buyers.

On Dec. 14, 2011, Gregory and Nina Logan were charged with violating the Wild Animal and Plant Protection and Regulation of International and Interprovincial Trade Act (WAPPRIITA). The case focused on approximately 250 tusks and eight different U.S. buyers (not all were charged), involving 46 different transactions over seven years, for which Logan was paid nearly $700,000, representing a profit of $385,000. After plea negotiations between the Crown attorney in Saint John and Logan’s lawyer, Brian Greenspan, Nina Logan’s charges were withdrawn and her husband’s dropped to seven.

Two years later, on Feb. 1, 2014, Logan was sentenced to four months of house arrest followed by four months under a curfew as well as a fine of $385,000, the highest ever levied under WAPPRIITA. He was also prohibited from possessing or purchasing marine mammal products for 10 years, and he lost the truck and a trailer he’d used to transport tusks to the U.S. As this issue of Canadian Wildlife went to press, he was fighting an extradition request by the U.S. Department of Justice to stand trial there. Greenspan argues that the charges are essentially the same as those he was convicted of in Canada, which would violate Logan’s Charter right not to be subjected to “double jeopardy” — being convicted twice for the same offence.

As for Operation Longtooth itself, it stands as a dramatic example of the challenge of enforcing laws to protect wildlife and the international complexities it can involve. At the same time, it stands as an example of what can be achieved — and potent reminder of why it matters.

Check your December issue of Wildlife Update for the continuation of this fascinating story!

Reprinted from Canadian Wildlife magazine. Get more information or subscribe now! Now on newsstands! Or, get your digital edition today!

- 0